|

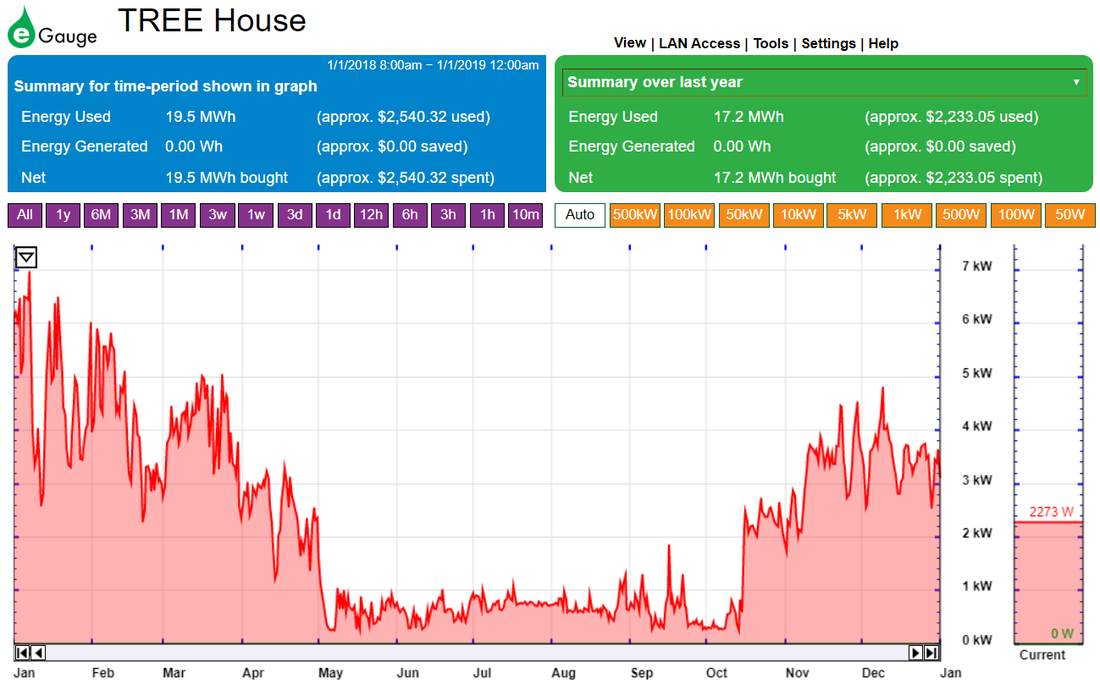

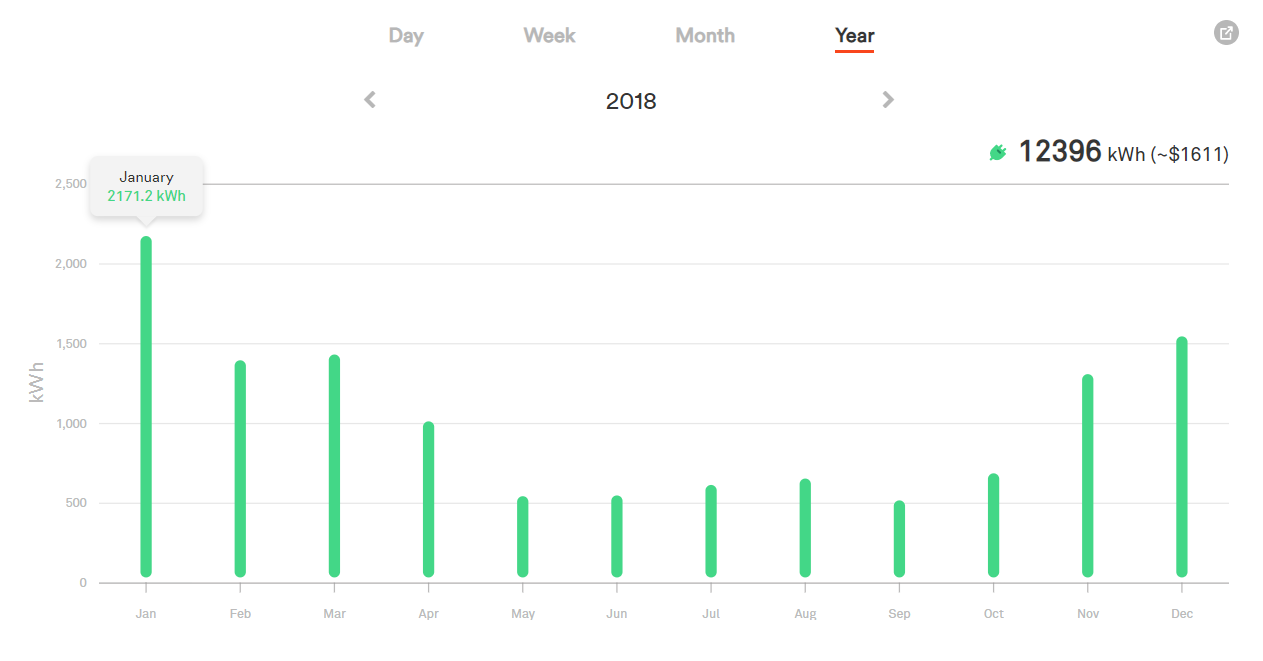

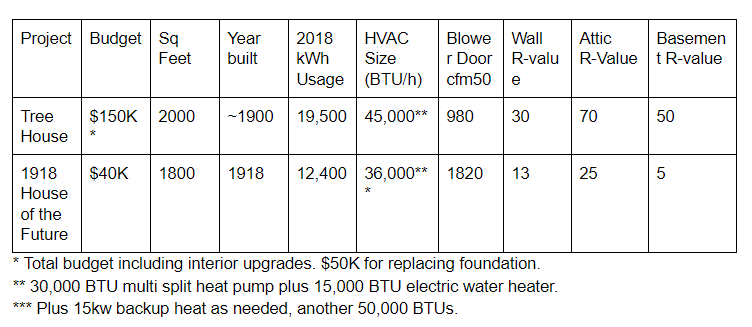

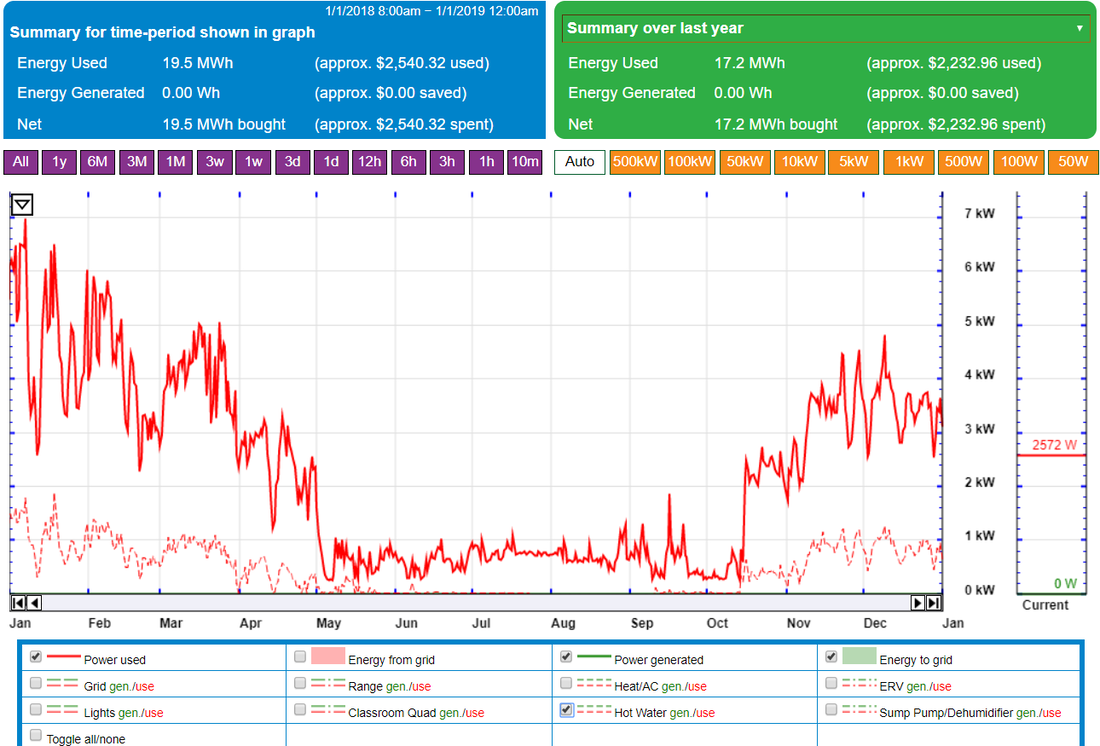

Want to know something crazy about the deep energy retrofit of this building? It uses 35-45% more energy than one of our much less deep projects. That’s one of the things we learned from the Hiram College TREE House project. Last time we talked about lessons learned about the dust and dehumidification air quality challenges, the comfort challenges caused by fresh air being introduced without being heated or cooling in the classroom, the second floor overheating because of closed office doors with mini split heads in them, and cooling challenges caused by multi-head mini split heat pumps. These are all pretty common practices in deep energy retrofits, ones that we challenge with our typical projects. That doesn’t mean either is right or wrong, but the more you understand, the better the job you can do on design on your own projects. In the case of the TREE House, a little more thought into placement of the heads and a larger, higher performance mini split heat pump could have changed the results a lot. This time we’ll compare two of our projects looking at energy use, insulation, and HVAC. Energy Use I already dropped the bombshell, this deep energy retrofit got its butt kicked by a much simpler project. Here’s the 2018 usage for the TREE House, 19,500 kilowatt hours. Winter looms large as you might expect, January and February are the coldest months here in Cleveland. Note that despite school starting 6 weeks earlier, usage doesn’t tick up until mid-October when the weather turned. This indicates that occupants don’t affect usage much. 1918 House of the Future Project Now let’s look at the 1918 House of the Future project. You can read much more about both projects in the highly detailed case studies at energysmartohio.com. The 1890 and 1900 case studies are also electrifications, we’re presently working on electrifications 11 and 12 - heat pumps work well even in cold climates. The usage data for this house is from the Sense energy monitor, check out my YouTube channel for a more detailed look at both of these monitors. Here’s a high level comparison of the overall projects, then we’ll dig deeper. Note the drastic difference between energy use. It’s been consistent, the TREE House uses 35-45% more than the 1918 House of the Future despite being only 10% larger and having a far better insulation package on paper. This is pretty wild because no one actually lives at the TREE House, so there is almost no hot water or cooking usage, and lighting usage is presumably lower because it’s needed less during daylight working hours. Let’s dig deeper into the projects. The TREE House Insulation Package I have to say, the insulation package is intense:

During the design charettes for the TREE House, we had advocated against doing exterior insulation, we thought it was too costly for the benefits. I don’t know what it models for this house, but on my old house a $75K exterior insulation job modeled $250/year in savings. That said, the new siding does make the house very attractive, where it used to be rather dumpy looking. 1918 House of the Future Insulation Package

In doing a lot of energy modeling, we’ve noticed that the value of R-value (pun intended) is severely overblown. The 1918 project has ⅓-½ the R-values of the super insulated TREE House, yet still outperforms it substantially. Why? Heating and cooling (HVAC) is the biggest piece. Let’s look at that. TREE House HVAC

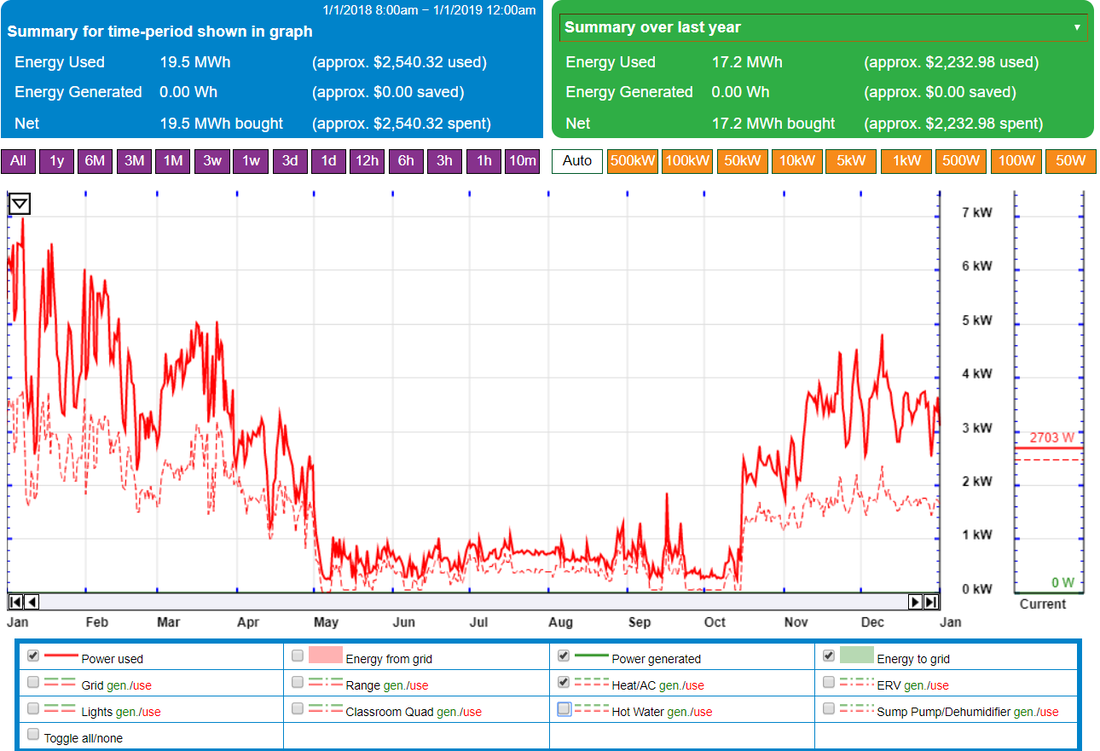

A boiler was installed for basement floor heat, but it was supposed to be a “kombi” boiler that does both space heat and hot water. Unfortunately the wrong one was installed, so we opted to remove the boiler entirely and replace it with a heat pump water heater. That allowed us to remove the gas meter, our first full electrification - many thanks to Dr. Debbie Kasper for the leap of faith on that one! Unfortunately, this requires the resistance element in the heat pump water heater to carry much of the load of the house since the heat pump scavenges heat from inside the building, not outside. If a larger more efficient heat pump had been used and one head was put in the basement, the energy use of the building would probably be similar to the 1918 House of the Future. When the basement is turned into a classroom, the plan is to add another mini split system there. Here is the usage of the heat pump, represented by the dotted line below the overall usage line. You can see it’s the majority of the usage of the home. And here is the water heater which heats the basement floor: It’s difficult to extract the exact energy usage from eGauge energy monitor reports, but these two charts show that HVAC is the predominant energy user. It should be noted that this mini split heat pump has mediocre performance amongst it’s brethren, better models are in the 10.5-11 HSPF range compared to the 8.5 for this one. It’s only a $1-2K cost difference, so a missed opportunity on a project with a high budget like this one. 1918 House of the Future HVAC

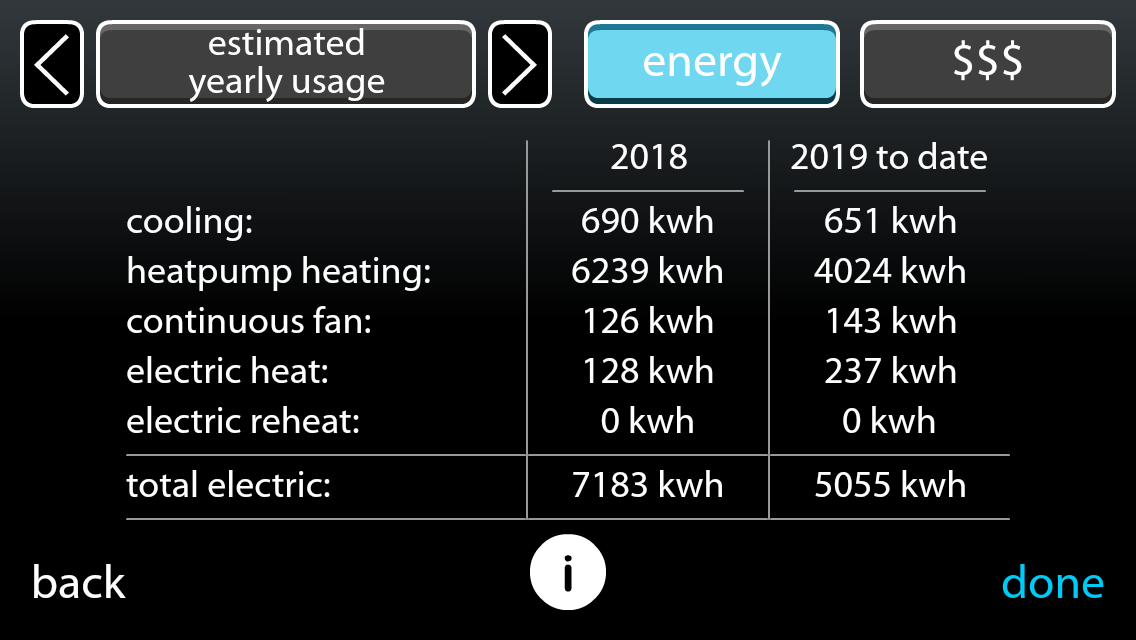

This particular heat pump is also capable of reheat dehumidification, a major part of BAD ASS HVAC. BAD ASS HVAC works for most new and existing homes in most climates, provides excellent comfort and IAQ, and happens to be all electric. I’ll introduce it early next year. This system also offers whole house filtration to knock contaminants out of the air, something mini splits can’t do well. This particular home did not get fresh air capability though, which can be seen in Foobot air quality monitor reports. Another nice thing about the Carrier GreenSpeed and its wifi thermostat is that you can track energy use by the day, month, and year, as well as by function - heating, cooling, backup heat, and reheat dehumidification. This house has proven to be a miser, as you can see in this 11/9/19 screenshot. I have thousands of screen shots watching these heat pumps operate. They are remarkable machines. For reference, our old house used about 12,000 kwh/year PLUS 1800 therms of gas. (1,000 of that was the heat pump water heater, 3,000 was for charging my Chevy Volt.) This house is using 12,400 total without gas!

Market Implications To me, this is the cool part. $150K demonstration projects are great, but they’re not scalable. This house is worth $200-225K, and this project didn’t add anywhere near the cost to its value. For a homeowner looking to retire someday, this is a poor use of capital. The good news is that we don’t have to go anywhere near that far to get killer results. In fact, smaller projects can deliver better results, as you’ve seen. While a $40K project is not inexpensive, it’s less than a typical kitchen remodel. We find that effective projects can be done for $100-200/month or $15-30K, which many households can afford. More importantly, these projects help solve problems consumers care about like hot and cold rooms, mold, reducing asthma and allergies, and more. Every client has different concerns and budget constraints, and every house has different needs. You have to solve for all three to get a viable project. Creating viable projects at scale is a serious challenge, frankly one that no one has figured out yet. We’re working on it though, and we think we’re very close. We’ve been developing a system for this called HVAC 2.0, in 2020 we'll be rolling it out and expanding to a nationwide network of HVAC contractors. In the meantime, I hope this series has helped you to question traditional deep energy retrofits. They have their place and they’ve taught us a lot, but we can get similar, often better, results with much less deep projects that have a real chance at scale. |

AuthorNate Adams is fiercely determined to get feedback on every project to learn more about what works and what doesn't. This blog shows that learning process. |

ServicesCompany |

Buy The Home Comfort Book!

© COPYRIGHT 2017. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed